Unit Testing, Scenarios and Categories: The SCAN Method

The art of unit testing lies in choosing a set of scenarios that will produce a high degree of confidence in the functioning of the unit under test across the often very large range of possible inputs.

This article discusses how to do this, and proposes a method introduced in a recent GitHub project, called Scenario Category ANalysis, or SCAN for short.

We begin with a section on background that includes a link to a 2018 presentation on unit testing that introduced the concept of domain partitioning as a way of breaking infinite input spaces into a finite set of subspaces. This concept is explained here, followed by a discussion of how domain categories can form the basis for a practical approach to breaking up the input space. There is a section with examples of use of category sets to develop unit test scenarios taken from a range of my own Oracle GitHub projects.

Next, Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN) is outlined as a systematic method for deriving unit test scenarios. We conclude with a section showing the application of the method to three examples using base code from third-party articles, taken from the GitHub project on the SCAN method.

There is an mp4 recording briefly (2m13s) going through the sections of this blog post:

[Update 16 April 2023: Added Mapping Scenarios to Categories 1-1]

Contents

↓ Background

↓ Domain Partitioning

↓ Domain Categories

↓ Generic Category Sets

↓ Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

↓ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

↓ SCAN Examples Of Use

↑ Mapping Scenarios to Categories 1-1

↓ Conclusion

↓ See Also

Background

I created the Trapit Oracle PL/SQL unit testing module on GitHub in 2016, and explained the concepts involved in a presentation at the Oracle User Group Ireland Conference in March 2018:

In 2018 I named the approach ‘The Math Function Unit Testing design pattern’, and developed a JavaScript module supporting its use in JavaScript unit testing, and formatting unit test results in both text and HTML:

The module also formats unit test results produced by programs in any language that follow the pattern and produce a JSON results files in the required format. After creating the JavaScript module, I converted the original Oracle Trapit module to use JSON files for both input and output in the required format:

Since then, I have used the Oracle unit testing framework in testing my own Oracle code of various types. These examples are all available on my GitHub account, and include utility packages, such as for code timing, and a project intended to demonstrate unit testing (as well as instrumentation) of ‘business as usual’-type PL/SQL APIs using the publicly available Oracle HR demo schema.

These projects include lists of scenarios based on analysis of input data category sets. In a more recent project, I have extended the ideas behind this to create a systematic method for deriving scenarios, which I call the SCAN method, for Scenario Category ANalysis. The method is outlined in the project root, and then illustrated by its application to three subprojects.

This article extracts from that project the outline of the SCAN method and its application to the three examples included.

Domain Partitioning

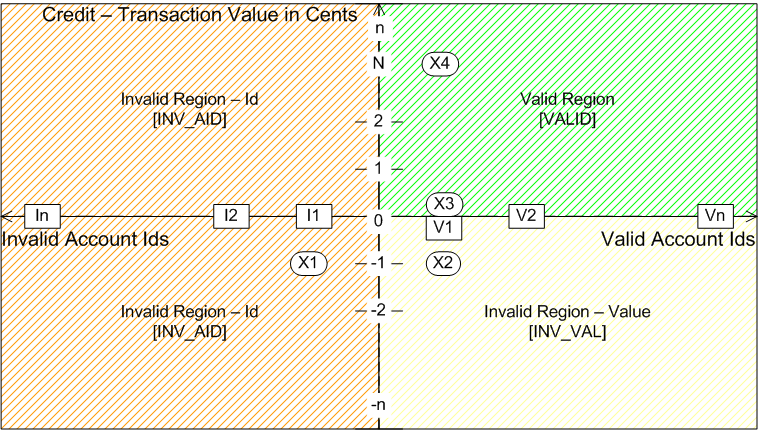

On March 23, 2018 I made a presentation at the Oracle User Group conference in Dublin, Database API Viewed As A Mathematical Function: Insights into Testing – OUG Ireland Conference 2018. In this presentation, I have a section ‘Test Coverage by Domain Partitioning’, in which I explain the concept of domain partitioning for test analysis. The idea here is to think of the unit under test as being a way of mapping from an input space to an output space, similar to a mathematical function. Testing is then a question of ensuring that for any given input, the unit returns the correct output. The concept of partitioning allows us to solve the obvious problem with this, that the input space is often effectively infinite. Although the number of possible inputs may be infinite, the number of distinct behaviours is not, and is usually quite small. In the presentation I used the example of a simple validation program for a credit card transaction, illustrated by this diagram:

The x-axis repreesnts possible account ids, and the y-axis allowable values for valid accounts. The validator should return one of three statuses:

- INV_AID - Invalid account id

- INV_VAL - Invalid amount

- VALID - Valid account id and amount

The diagram depicts a partioning of the input space into three regions, corresponding to the different statuses the validator is expected to return. We can easily see how this simple program could be effectively tested using a small number of sample input points. Four points are shown on the diagram:

- X1 - (I1, -1) - Invalid account id (amount irrelevant): INV_AID

- X2 - (V1, -1) - Valid account id, invalid amount (smallest possible): INV_VAL

- X3 - (V1, 0) - Valid account id, valid amount (smallest possible): VALID

- X4 - (V1, N) - Valid account id, valid amount (large amount): VALID

We can categorize the possible values for the two parameters into valid and invalid sets. For the account id, validity is defined simply as being in a given set of valid account ids, or not. We can test this with two points, one having an invalid account id, and any amount (X1), and one having both a valid account id and a valid amount (which may depend on the account id) (X3).

For the amount, we want to test that amounts that go above the available credit limit are rejected, while those that remain within it are accepted, for any given valid account id. Despite the infinite number range available for amount, we can effectively test this with 3 data points. We want to check behaviour in each of the two regions (valid and invalid), and also that the crossover point is correct. To do this we use one point (X2) that is just invalid and another that is just valid (X3), both having a valid account id. However, as well as the explicit functional requirements, we should also be aware of possible behaviour changes for technical reasons: For example, a very large amount could cause a numeric overflow. We should include data points to test any such possibilities identified. In this case, we could decide the largest possible amount that the program needs to be able to handle and use that (X4). We can reasonably assume, although not prove, that if X3 and X4 behave correctly then points with amounts in between should do so too.

Domain Categories

↑ Contents

↓ Independent Categories

↓ Inter-dependent Categories

↓ Category Sets

For the simple 2-parameter case discussed above we can visualize the idea of domain partitioning, as in the 2-dimensional diagram shown. For larger numbers of parameters we can’t so easily visualize the domains in this way. It may then be better to think more in terms of domain, or subdomain, categories. Usually, large numbers of parameters do not need to considered simultaneously and we can decompose the domain space into individual, or small sets of, variables.

Then we can divide these lower-dimensional spaces into categories, with category corresponding to subdomain partition and location within the partition. Program behaviour would be expected to be essentially the same within a category, but could differ across categories for either functional requirement or potentially differ for technical reasons.

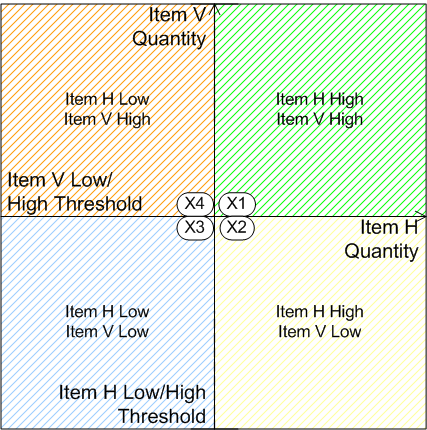

In this way we can obtain small sets of sample data that test behaviour effectively over all categories within a given subdomain, despite the input space being infinite. Where subdomains are behaviourally independent we can test them together by combining the subdomain data points into a single overall scenario that tests one behaviour for each subdomain. My 2018 presentation mentioned earlier discusses these subjects, with examples, in the section ‘Test Coverage by Domain Partitioning’. Here is an example taken from there of unit pricing for two distinct items in a sales order context, where the unit price is banded according to quantity. Each quantity for the two items, say Item H and Item V, has two categories: Low and High.

In order to test banding behaviour around the band thresholds we need to take as test data points with quantities just either side of the thresholds for each item, shown as X1-X4 on the diagram. We will generally also want to test at the other boundaries of the partitions, which will sometimes be implicit - for example, how large a numeric value do we need the program to work for without hitting any technical limit such as a maximum number value. For now, we’ll consider just the intersection shown.

Independent Categories

If the unit price for Item H depends only on the quantity for Item H and the same for Item V, then we need only test two scenarios - either the pair of data point (X1, X3) or the pair (X2, X4).

We have two categories for each item:

Item H

- Item H - Low (X3 and X4)

- Item H - High (X1 and X2)

Item V

- Item V - Low (X2 and X3)

- Item V - High (X1 and X4)

Inter-dependent Categories

If the unit price for Item H depends on the quantities for both Item H and Item V, and the same for Item V, then we need to test four scenarios - (X1, X2, X3, X4).

We have four categories for the item pair:

- Item H - Low / Item V - Low (X3)

- Item H - High / Item V - Low (X2)

- Item H - Low / Item V - High (X4)

- Item H - High / Item V - High (X1)

Category Sets

In this simple example, we have been considering a single set of categories, applying either to each dimension separately, or to the 2-dimensional pair. More generally, we may have many parameters (or other inputs), and it will be convenient to separate into category sets containing the categories of a single kind applying to one or more inputs, or some function of the inputs. This will become clearer in the examples section below.

Generic Category Sets

↑ Contents

↓ Value Size: Small and Large

↓ Value Multiplicity: Few and Many

↓ Validity Status: Valid/Exceptions

↓ List Multiplicity: Zero / One / Multiple

The initial task of unit test analysis, where we try to find a set of data points (‘scenarios’) that will test all behaviours, amounts to finding all relevant domain category sets and choosing the data points accordingly. It’s often extremely helpful to consider some generic category sets that are widely applicable.

In unit testing this GitHub module, Oracle PL/SQL general utilities module, the unit under test is taken to be a wrapper function that calls each of the program units independently. Four generic scenarios were used in testing, as shown below. We’ll use this example to illustrate the first three category sets considered below. The fourth will use a different example based on testing an SQL query as a view.

Unit Test Report: utils

=======================

# Scenario Fails (of 15) Status

--- -------- ------------- -------

1 Small 0 SUCCESS

2 Large 0 SUCCESS

3 Many 0 SUCCESS

4 Bad SQL 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 4: SUCCESS

======================================

In the first three sections below we show the inputs and outputs for two utility functions for the above scenarios, extracted from the unit test results text file utils.txt (there are also HTML versions in the module).

- Join_Values - returns a string of comma-separated values for an input set of paramater values

- Split_Values - returns a list of values for an input string of comma-separated values

Value Size: Small and Large

Input values can often be categorized as Large or Small, and program bugs often occur when a value is larger than the program can handle, so it makes sense to test with values at least as large as are expected to be encountered. For numeric values very small numbers can also cause problems, and they can be similarly tested where applicable.

The category Small can sometimes be combined with the category Few within the Value Multiplicity category set, as in our example below, in which csv strings with only one value are special in having no delimiters, so may be worth testing explicitly.

In the example below, we supply a single short value as a parameter to the function Join_Values for the Small category, which is the minimum number of parameters, and the same value to the function Split_Values. For the Large category, we add a second value of length 100.

SCENARIO 1: Small/Few

INPUTS

======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Value 1 Value 2 Value 3 Value 4 Value 5 Value 6 Value 7 Value 8 Value 9 Value 10 Value 11 Value 12 Value 13 Value 14 Value 15 Value 16 Value 17

- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

1 value1

}

=

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Delimited String

- ----------------

1 value1

}

=

OUTPUTS

=======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Delimited String

- ----------------

1 value1

} 0 failed of 1: SUCCESS

========================

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Value

- ------

1 value1

} 0 failed of 1: SUCCESS

========================

SCENARIO 2: Large

INPUTS

======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Value 1 Value 2 Value 3 Value 4 Value 5 Value 6 Value 7 Value 8 Value 9 Value 10 Value 11 Value 12 Value 13 Value 14 Value 15 Value 16 Value 17

- ------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

1 value1 1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890

}

=

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Delimited String

- -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 value1,1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890

}

=

OUTPUTS

=======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Delimited String

- -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 value1,1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890

} 0 failed of 1: SUCCESS

========================

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Value

- ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 value1

2 1234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890123456789012345678901234567890

} 0 failed of 2: SUCCESS

========================

Value Multiplicity: Few and Many

Input values can often be categorized as Few or Many, and program bugs often occur when there are more values than the program can handle, so it makes sense to test with at least as many values as are expected to be encountered. If we also test for the smallest number of values, we can be confident across the range of this aspect of the program’s functioning.

In the example below, we supply 17 values as separate parameters to the function Join_Values for the Many category, while one value, the minimum number, was supplied under the category Small in the previous section. We supply 50 values to the Split_Values function in csv format, which returns the 50 values as an array.

SCENARIO 3: Many

INPUTS

======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Value 1 Value 2 Value 3 Value 4 Value 5 Value 6 Value 7 Value 8 Value 9 Value 10 Value 11 Value 12 Value 13 Value 14 Value 15 Value 16 Value 17

- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- ------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- -------- --------

1 v01 v02 v03 v04 v05 v06 v07 v08 v09 v10 v11 v12 v13 v14 v15 v16 v17

}

=

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Delimited String

- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 v01|v02|v03|v04|v05|v06|v07|v08|v09|v10|v11|v12|v13|v14|v15|v16|v17|v18|v19|v20|v21|v22|v23|v24|v25|v26|v27|v28|v29|v30|v31|v32|v33|v34|v35|v36|v37|v38|v39|v40|v41|v42|v43|v44|v45|v46|v47|v48|v49|v50

}

=

OUTPUTS

=======

GROUP 5: Join Values (scalars) {

================================

# Delimited String

- -------------------------------------------------------------------

1 v01|v02|v03|v04|v05|v06|v07|v08|v09|v10|v11|v12|v13|v14|v15|v16|v17

} 0 failed of 1: SUCCESS

========================

GROUP 6: Split Values {

=======================

# Value

-- -----

1 v01

2 v02

3 v03

4 v04

5 v05

6 v06

7 v07

8 v08

9 v09

10 v10

11 v11

12 v12

13 v13

14 v14

15 v15

16 v16

17 v17

18 v18

19 v19

20 v20

21 v21

22 v22

23 v23

24 v24

25 v25

26 v26

27 v27

28 v28

29 v29

30 v30

31 v31

32 v32

33 v33

34 v34

35 v35

36 v36

37 v37

38 v38

39 v39

40 v40

41 v41

42 v42

43 v43

44 v44

45 v45

46 v46

47 v47

48 v48

49 v49

50 v50

} 0 failed of 50: SUCCESS

=========================

Validity Status: Valid/Exceptions

Validity status and exception handling is a very general category set for unit testing. It’s illustrated here by a scenario in which an invalid view name is passed to one function, and an invalid string of cursor text is passed to another. The two functions tested are:

- View_To_List - returns a string of comma-separated values for an input view name

- Cursor_To_List - returns a list of comma-separated values for an input ref cursor

SCENARIO 4: Bad SQL

INPUTS

======

GROUP 7: View To List {

=======================

# Select Column Name

- ------------------

1 type_name

}

=

GROUP 8: Cursor To List {

=========================

# Cursor Text Filter

- ----------------------------------------------- -----------------------------

1 select type_name from BAD_user_types order by 1 (CHR|L\d).+(ARR|REC)|TT_UNITS

}

=

GROUP 12: Scalars {

===================

# Delimiter View Name View Where View Order By W Line

- --------- -------------- ------------------------------------------------------- ------------- ------

1 , BAD_user_types regexp_like(type_name, '(CHR|L\d).+(ARR|REC)|TT_UNITS')

}

=

OUTPUTS

=======

GROUP 11: Exception {

=====================

# Source Message

- -------------- ---------------------------------------

1 view_To_List ORA-00942: table or view does not exist

2 cursor_To_List ORA-00942: table or view does not exist

} 0 failed of 2: SUCCESS

========================

List Multiplicity: Zero / One / Multiple

When lists are processed, there are often differences in behaviour depending on whether the list is empty, has one element, or has more than one element. For example, in SQL joins an inner join to a row source that is empty suppresses the driving row, whereas an outer join retains it and pads the joined fields with blanks.

Also, joining a row to multiple rows causes the driving row to be duplicated for each of the joined rows. Sometimes this is desired, but other times it’s not, and undesired record duplication is a not uncommon reporting bug.

It’s therefore a good idea to test these different categories explicitly where applicable. We’ll take as an example of testing inner and outer joins the first scenario from another GitHub project of mine, Oracle PL/SQL API Demos, that uses Oracle’s HR demo schema. This involves testing an SQL query in the form of a view.

In the view, the manager is outer-joined to the employee, while the department is inner-joined. This explains why employee LN_1, with no manager, is included, while employee LN_3, with no department, is excluded (LN_4 is excluded for another reason). The text below is extracted from tt_view_drivers.hr_test_view_v.txt.

Unit Test Report: TT_View_Drivers.HR_Test_View_V

================================================

# Scenario Fails (of 1) Status

--- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------ -------

1 DS-1, testing inner, outer joins, analytic over dep, and global ratios with 1 dep 0 SUCCESS

2 DS-2, testing same as 1 but with extra emp in another dep 0 SUCCESS

3 DS-2, passing 'WHERE dep=10' 0 SUCCESS

4 DS-3, Salaries total 1500 (< threshold of 1600, so return nothing) 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 4: SUCCESS

======================================

SCENARIO 1: DS-1, testing inner, outer joins, analytic over dep, and global ratios with 1 dep {

===============================================================================================

INPUTS

======

GROUP 1: Employee {

===================

# Employee Id Last Name Email Hire Date Job Salary Manager Id Department Id Updated

- ----------- --------- ----- ----------- ------- ------ ---------- ------------- -----------

1 2618 LN_1 EM_1 17-JUN-2018 IT_PROG 1000 10 17-JUN-2018

2 2619 LN_2 EM_2 17-JUN-2018 IT_PROG 2000 2618 10 17-JUN-2018

3 2620 LN_3 EM_3 17-JUN-2018 IT_PROG 3000 2618 17-JUN-2018

4 2621 LN_4 EM_4 17-JUN-2018 AD_ASST 4000 2618 10 17-JUN-2018

}

=

GROUP 2: Where {

================

# Where

- -----

1

}

=

OUTPUTS

=======

GROUP 1: Select results {

=========================

# Name Department Manager Salary Salary Ratio (dep) Salary Ratio (overall)

- ---- -------------- ------- ------ ------------------ ----------------------

1 LN_1 Administration 1000 .67 .4

2 LN_2 Administration LN_1 2000 1.33 .8

} 0 failed of 2: SUCCESS

========================

} 0 failed of 1: SUCCESS

========================

Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

↑ Contents

↓ Oracle PL/SQL API Demos

↓ Oracle PL/SQL Code Timing

↓ Oracle Logging

↓ Oracle PL/SQL Network Analysis Function

In this section we will look at some examples of lists of scenarios from the unit test summary pages of some of my own GitHub projects, and briefly note how the scenarios explore different categories within the data.

Oracle PL/SQL API Demos

↑ Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

↓ TT_Emp_WS.Save_Emps

↓ TT_Emp_Batch.Load_Emps

- GitHub: Oracle PL/SQL API Demos

This project demonstrates instrumentation and logging, code timing and unit testing of Oracle PL/SQL APIs, and was already used in one of the examples above. We’ll take two more of the entry point procedures here for further illustration of unit test scenarios.

TT_Emp_WS.Save_Emps

The unit here is a procedure that saves employee records to the database, of a kind that might be called by a web service.

- Validity status

- Valid record - as often happens, the first scenario is a simple base case where a single valid record is saved

- Two categories of invalid record - scenarios 2 and 3

- Invalid record is rejected, but valid ones saved - scenario 4

- List multiplicity

- One valid record - scenario 1

- Multiple valid records - scenario 4

Unit Test Report: TT_Emp_WS.Save_Emps

=====================================

# Scenario Fails (of 3) Status

--- ------------------------------------------------------- ------------ -------

1 1 valid record 0 SUCCESS

2 1 invalid job id 0 SUCCESS

3 1 invalid number 0 SUCCESS

4* 2 valid records, 1 invalid job id (2 deliberate errors) 1 FAILURE

Test scenarios: 1 failed of 4: FAILURE

======================================

TT_Emp_Batch.Load_Emps

The unit here is a procedure that loads employee records to the database from an input file, of a kind that might be called in batch mode.

To help organise scenarios and obtain good coverage of combinations of categories, the scenario description includes counts of records in various categories, the first two being counted in pairs:

- Input employees by age

- N - New

- O - Old (not updated)

- OU - Old (updated)

- Input employees by validity

- V - Valid

- I - Invalid

- Pre-existing records in table

- J - Job Statistics

- E - Employees

Some scenarios result in an exception being raised, and others do not, with invalid employees being saved to an errors table instead, and this is noted in the scenario descriptiun. An input parameter controls a percentage failure threshold for this category:

- Fail Percent

- Over - raise exception 'ORA-20000: Batch failed with too many invalid records!'

- Under - no exception, insert invalid records to errors table

Unit Test Report: TT_Emp_Batch.Load_Emps

========================================

# Scenario Fails (of 4) Status

--- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------ -------

1 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 1/0/0/0/0/0. Existing J/E: 0/0. [1 valid new record from scratch] 0 SUCCESS

2 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 1/1/1/0/0/0. Existing J/E: 1/0. [3 valid records of each kind] 0 SUCCESS

3 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/0/0/0/1/0. Existing J/E: 1/1. Uid not found [1 invalid old - exception] 0 SUCCESS

4 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/0/0/1/0/0. Existing J/E: 1/1. Email too long [1 invalid new - exception] 0 SUCCESS

5 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 1/0/0/0/1/0. Existing J/E: 1/1. Name too long [1 valid new, 1 invalid old - no exception] 0 SUCCESS

6 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/0/0/1/0/0. Existing J/E: 1/1. Invalid job [1 invalid new - exception] 0 SUCCESS

7 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/1/0/1/1/0. Existing J/E: 1/2. 2 invalid jobs [1 valid old, 2 invalid: old and new - no exception] 0 SUCCESS

8 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/1/0/0/0/1. Existing J/E: 1/2. Name 4001ch [1 valid old, 1 invalid new for external table - no exception; also file had previously failed] 0 SUCCESS

9 NV/OV/OU/NI/OI/EI: 0/0/0/1/0/0. Existing J/E: 1/1. [File already processed - exception] 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 9: SUCCESS

======================================

Oracle PL/SQL Code Timing

↑ Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

- GitHub: Oracle PL/SQL Code Timing

This project contains a PL/SQL package for code timing with timer sets, and is used for program instrumentation. A timer set is constructed, then named timers within the set are used to aggregate CPU and elapsed times and calls across sections of code. Multiple timer sets can be in use simultaneously.

This is a situation in which the public methods for constructing a set, incrementing timers and reporting the results work together to give meaningful outputs. It raises the question of what ‘unit’ we should unit test, since the individual methods operate in the context of in-memory data structures that are not direct inputs or outputs. In fact the Math Function Unit Testing design pattern provides a very effective conceptual framework to answer that question.

The answer is that we construct a wrapper function that simulates a session in which the package is used to construct and report on one or more timer sets. The function is ‘externally’ pure, taking as input a stream of events that correspond to method invocations, and some scalar parameters, and as output the return values from the reporting methods applied to up to two timer sets.

In order to check the aggregation precisely mocked values are used in some scenarios since real times are indeterminate. On the other hand we need also to check functioning in the normal case where timings come from Oracle API calls, in which case we specify expected results as ranges. This leads to the first category:

- Mocked

- No - times used are the Oracle timing APIs' call values (scenario 2). The self-timer method is tested here

- Yes - times used are passed in with the event sequence (other scenarios)

We want to ensure that timing functions correctly across a range of scales, so test at the extremes of interest, using mocked times to facilitate.

- Large and small times

- Large - scenario 3 has elapsed/CPU times of 20,000/4,000 seconds

- Small - scenario 4 has elapsed/CPU times of 0.01/0.08 seconds

Parameters controlling display formats are defaulted, and we want to check both defaults and specified values work. The defaults are largely independent so we can test in parallel.

- Defaulting

- Defaulted - scenario 1 has defaults for format widths and decimal places

- Non-Defaulted - scenario 5 passes non-default widths and decimal places

Timer sets need to operate independently, so we must test with two sets as well as with one. The first scenario test two sets, and also ensures that all reporting methods are tested, except the self-timer.

- Timer set multiplicity

- Multiple timer sets - scenario 1 has two sets with interleaved method calls

- One timer set - other scenarios use a single timer set

- Zero timers - scenario 5 is an edge case with no timers

Timer sets need to operate independently, so we must test with two sets as well as with one. The first scenario test two sets, and also ensures that all reporting methods are tested, except the self-timer.

- Timer multiplicity

- Multiple timers - scenario 1 has two sets with interleaved method calls

- One timer - other scenarios use a single timer set

- Zero timers - scenario 5 is an edge case with no timers

Parameters passed must be consistent, otherwise an exception should be raised. Categories where an exception is raised will generally require a scenario each, rather than being combined with other category tests.

- Exceptions

- Invalid parameters - scenario 7 passes inconsistent parameters, exception raised - 'ORA-20000: Error, time_width + time_dp must be >= 6, actual: 4 + 1'

- Valid parameters - other scenarios do not raise an exception

Unit Test Report: timer_set

===========================

# Scenario Fails (of 8) Status

--- ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------ -------

1 2 timer sets, ts-1: timer-1 called twice, timer-2 called in between; ts-2: timer-1 called twice, initTime called in between; all outputs; mocked 0 SUCCESS

2 As scenario 1 but not mocked, and with SELFs 0 SUCCESS

3 Large numbers, mocked 0 SUCCESS

4 Small numbers, mocked 0 SUCCESS

5 Non-default DP, mocked 0 SUCCESS

6 Zero DP, mocked 0 SUCCESS

7 Error DP, mocked 0 SUCCESS

8 Timer Set with no timers 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 8: SUCCESS

======================================

Oracle Logging

↑ Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

- GitHub: Log_Set - Oracle logging module

This module is a framework for logging, that supports the writing of messages to log tables (and/or the Application Info views), along with various optional data items that may be specified as parameters or read at runtime via system calls. It was designed to be as flexible and configurable as possible, which leads to a lot of categories in unit testing.

There are a lot of possible defaults, overriding of most of which can be tested in parallel in one scenario.

- Defaulting

- Defaulted - scenario 1

- Non-Defaulted - scenario 3

Normal and large values for inputs are tested.

- Value size

- Normal - scenario 3

- Large - scenario 4

Multiple logs can be written to simultaneously.

- Log set multiplicity

- Multiple log sets - scenario 8 has 3 sets with interleaved method calls

- Single log set - scenario 1

Only one log of type Singleton can be written to, but other types can be written to alongside it.

- Singleton

- Singleton plus non-singleton ok - scenario 18

- Singleton plus singleton fails - scenario 19

Lists as well as scalar strings can be put, from the put method and also on construction.

- Putting lists

- Construct and Put lists - scenario 9

The logger allows for buffering of lines for performance.

- Array length parameters (check no lines unsaved)

- Default (unbuffered) - scenario 1

- Specific values - scenario 20

App Info refers to context information accessed via DBMS_Application_Info. The logger can ignore this, or set and store it, with or without also logging lines.

- App info

- None - scenario 1

- With lines - scenario 14

- Only - scenario 13

The logger includes an error handling procedure to be called in WHEN OTHERS block, and it can write to an exiting log or create a new one.

- OTHERS error handler

- Existing log - scenario 15

- New log - scenario 16

An existing config can be used, or a new one created.

- New/Existing config

- New - scenario 5

- Existing - scenario 1

Oracle has various metadata items available in a system context, and the logger allows for named items to be stored at header or line level, or both, or not to be stored, according to config.

- Context level

- None - scenario 1

- Header - scenario 5

- Line - scenario 5

- Both - scenario 5

Entry and exit point procedures wrap default construction and closing of logs for ease of use.

- Entry/exit point

- Entry/exit point calls work - scenario 21

There are a number of validations that can raise exceptions.

- Validity status

- Valid - scenario 1

- Closed log id - scenario 10

- Invalid log id - scenario 11

- Invalid log config - scenario 12

Unit Test Report: log_set

=========================

# Scenario Fails (of 5) Status

--- -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------ -------

1 Simple defaulted 0 SUCCESS

2 Simple defaulted, don't close - still saved with default buffer size = 1 0 SUCCESS

3 Set all parameters 0 SUCCESS

4 Set all parameters with long values 0 SUCCESS

5 New config, with H/B/L contexts and parameters all passed; module app info 0 SUCCESS

6 New config, with H/B/L contexts; put level prints only some lines; field min put levels below line min - should print; line close 0 SUCCESS

7 New config; field min put levels above line min - should not print; header min level above module level, module/action to put (but not client info); contexts not to print 0 SUCCESS

8 MULTIBUF: Three logs printing 2 lines interleaved, plus header only; also log that shouldn't print 0 SUCCESS

9 Construct and put lists 0 SUCCESS

10 Closed log id 0 SUCCESS

11 Invalid log id 0 SUCCESS

12 Invalid log config 0 SUCCESS

13 App info only 0 SUCCESS

14 App info without module, and writing to table 0 SUCCESS

15 OTHERS error handler, existing log 0 SUCCESS

16 OTHERS error handler, new log 0 SUCCESS

17 Custom error handler, existing log 0 SUCCESS

18 Singleton (pass null log id) plus non-singleton 0 SUCCESS

19 Singleton (pass null log id) plus singleton - fails 0 SUCCESS

20 Array length parameters (check no lines unsaved) 0 SUCCESS

21 Entry/Exit Point 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 21: SUCCESS

=======================================

Oracle PL/SQL Network Analysis Function

↑ Unit Test Scenarios and Category Sets: Some Examples

- GitHub: Oracle PL/SQL Network Analysis

The module contains a PL/SQL package for the efficient analysis of networks that can be specified by a view representing their node pair links. The package has a pipelined function that returns a record for each link in all connected subnetworks, with the root node id used to identify the subnetwork that a link belongs to.

- Multiplicity of Subnetworks

- One subnetwork - scenarios 1, 2

- Multiple subnetworks - scenario 3 has 4

- Value size

- Small - scenarios 1, 3

- Large - scenario 2 has 100 character node names

- Subnetwork structure

- Simple tree - scenario 1 has a single link

- Self-linked loop - scenario 2 has a single node looped subnetwork

- 2-node loop - scenario 3 has a 2-node looped subnetwork

- 3-node loop - scenario 3 has a 3-node looped subnetwork

- Linear tree - scenario 3 has a linear 3-node tree subnetwork

- Nonlinear tree - scenario 3 has a nonlinear 4-node tree subnetwork

Unit Test Report: Net_Pipe

==========================

# Scenario Fails (of 1) Status

--- ------------------------------ ------------ -------

1 1 link 0 SUCCESS

2 1 loop, 100ch names 0 SUCCESS

3 4 subnetworks, looped and tree 0 SUCCESS

Test scenarios: 0 failed of 3: SUCCESS

======================================

Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

↑ Contents

↓ Input Data Category Sets

↓ Simple Category Sets

↓ Composite Category Sets

↓ Scenario Category Mapping

- GitHub: Oracle Unit Test Examples

In the GitHub project above, I hardened the ideas around scenarios and categories in order to develop a systematic, almost algorithmic, procedure for obtaining a set of category-level scenarios from analysis of categories.

This section is extracted from the root project README, with the following examples section extracted from the three subproject READMEs.

Input Data Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category Analysis (SCAN)

In the proposed approach, we define category sets relevant to the unit under test, each having a finite set of categories. The aim is then to construct high level scenarios consisting of a combination of one category from each category set. The test data for the scenario is then constructed by choosing data points within the chosen categories.

While this approach reduces the size of the input space to be considered, the number of category combinations may still be large. If we write Ci for the cardinality of the i’th category set then the total number of combinations is the product of the cardinalities:

C_1.C2…CN for N category sets

So, if we had, say, just 3 category sets with 4 categories in each, we would have 43 = 64 combinations, and the numbers could be much larger in some cases. Fortunately, in practice we do not need to consider all combinatioons of categories, since many category sets are independent, meaning that we can test their categories in parallel. For example, a common generic category set could be value size for a given field, where we want to verify that both large and small values can be handled without errors. It would usually be reasonable to test small and large categories for all fields in parallel, requiring just two scenarios.

It may be helpful to start by tabulating the relevant simple category sets, before moving on to consider which sets also need to be considered in combination.

Simple Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

This section shows a simple generic way of tabulating a category set. We would create a similar table for each one relevant to the unit under test.

CST - Category set description

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Cat-1 | Description of category 1 |

| Cat-2 | Description of category 2 |

Composite Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

While many category sets can be tested independently of others as in the value size example mentioned above, in other cases we may need to consider categories in combination. For example, in the context of sales orders it is common for unit prices to be banded according to quantity ordered, and it is possible (though maybe not so common) for quantities of different items to affect each others’ unit prices.

CST-1-CST-2 - Category sets CST-1, CST-2 combinations

This section shows a simple generic way of tabulating a combination of category sets, where in this case all 4 combinations of 2 categories within 2 category sets are enumerated.

| CST-1 | CST-2 |

|---|---|

| Cat-11 | Cat-21 |

| Cat-12 | Cat-21 |

| Cat-11 | Cat-22 |

| Cat-12 | Cat-22 |

There may also be more complex dependencies. For example, we may have a master entity where the category chosen may limit the possible categories available to detail entities. In any case, the aim is to enumerate the possible combinations for the categories considered together; in fact we can consider the combinations to form a single composite category set in itself.

Scenario Category Mapping

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

Once we have identified the relevant category sets and enumerated the categories within them, we can produce a list of scenarios. If, as noted above, we consider all groups of inter-dependent category sets as category sets in their own right, with their categories being the possible combinations, and by definition independent of each other, we can easily see how to construct a comprehensive list of scenarios:

- Take the category set of highest cardinality and create a scenario record for each (possibly composite) category

- Use the category description, or combination of sub-category codes, as a unique identifier for the scenario

- Tabulate the list of scenarios with a number, the unique identifier columns and append the other independent category sets as columns

- The secondary category set columns enumerate their categories until exhausted, then repeat categories as necessary to complete the records

Here is a schematic for the kind of table we might construct, representing category level scenarios:

| # | CST-KEY | Description | CST-SEC-1 | ETC. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CAT-KEY-1 | CAT-KEY-1 description | CAT-SEC-1 | … |

| 2 | CAT-KEY-2 | CAT-KEY-2 description | CAT-SEC-2 | … |

Data points can then be constructed within the input JSON file to match the desired categories, to give the data level scenarios.

The discussion above is necessarily somewhat abstract, but the examples in the next section should make the approach clearer.

SCAN Examples Of Use

↑ Contents

↓ login_bursts

↓ sf_epa_investigations

↓ sf_sn_log_deathstar

- GitHub: Oracle Unit Test Examples

In the GitHub project above, I hardened the ideas around scenarios and categories in order to develop a systematic, almost algorithmic, procedure for obtaining a set of category-level scenarios from analysis of categories.

This section is extracted from the three subproject READMEs, while the preceding section is extracted from the root project README.

login_bursts

↑ SCAN Examples Of Use

↓ Example Data and Solution

↓ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

The login_bursts subproject concerns the problem of determining distinct ‘bursts of activity’, where an initial record defines the start of a burst, which then includes all activities within a fixed time interval of that start, with the first activity outside the burst defining the next burst, and so on.

Example Data and Solution

Example data

PERSONID LOGIN_TIME

---------- --------------

1 01012021 00:00

01012021 01:00

01012021 01:59

01012021 02:00

01012021 02:39

01012021 03:00

01012021 04:59

2 01012021 01:01

01012021 01:30

01012021 02:00

01012021 05:00

01012021 06:00

12 rows selected.

Solution for example data

PERSONID BLOCK_ST

---------- --------

1 01 00:00

01 02:39

01 04:59

2 01 01:01

01 05:00

Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

↑ login_bursts

↓ Simple Category Sets

↓ Composite Category Sets

↓ Scenario Category Mapping

In this section we identify the category sets for the problem, and tabulate the corresponding categories. We need to consider which category sets can be tested independently of each other, and which need to be considered in combination. We can then obtain a set of scenarios to cover all relevant combinations of categories.

Simple Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

MUL-P - Multiplicity for person

Check works correctly with both 1 and multiple persons.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | One |

| 2 | Multiple (2 sufficent to represent multiple) |

MUL-L - Multiplicity for login groups per person (or MUL-L1, MUL-L2 for person 1, person 2 etc.)

Check works correctly with both 1 and multiple logins per person.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | One login group per person |

| m | Multiple login groups per person |

SEP - Group separation

Check works correctly with groups that start shortly after, as well as a long time after, records in a prior group.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| S | Small |

| L | Large |

| B | Both large and small separations |

GAD - Group across days

Check works correctly when group crosses into another day.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Group within day |

| 2 | Group across 2 days |

SIM - Simultaneity

Check works correctly with simultaneous group start records.

| Simultaneous | Description |

|---|---|

| Y | Simultaneous records |

| N | No simultaneous records |

Composite Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

The multiplicities of persons and login groups need to be considered in combination.

MUL-PL - Multiplicity of persons and logins

Check works correctly with 1 and multiple persons and login groups per person.

| MUL-P | MUL-L1 | MUL-L2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | - |

| 1 | m | - |

| 2 | m | m |

Scenario Category Mapping

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

We now want to construct a set of scenarios based on the category sets identified, covering each individual category, and also covering combinations of categories that may interact.

In this case, the first three category sets may be considered as a single composite set with the combinations listed below forming the scenario keys, while the other three categories are covered in parallel.

| # | MUL-P | MUL-L1 | MUL-L2 | SEP | GAD | SIM | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | - | S | 1 | N | MUL-P / MUL-L1 / MUL-L2 / SEP / GAD / SIM = 1 / 1 / - / S / 1 / N |

| 2 | 1 | m | - | B | 2 | N | MUL-P / MUL-L1 / MUL-L2/ SEP / GAD / SIM = 1 / m / - / B / 2 / N |

| 3 | 2 | m | m | B | 1 | Y | MUL-P / MUL-L1 / MUL-L2 / SEP / GAD / SIM = 2 / m / m /B / 1 / Y |

sf_epa_investigations

↑ SCAN Examples Of Use

↓ Example Data and Solution

↓ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

The sf_epa_investigations subproject concerns the efficient allocation of identifiers for spray and pesticide against an investigation identifier, in the context of environmental inspection.

Example Data and Solution

Call procedure as example three times...

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

1 BEGIN

2 investigation_mgr.pack_details(

3 p_investigation_id => 100,

4 p_pesticide_id => 123,

5 p_spray_id => 789

6 );

7

8 investigation_mgr.pack_details(

9 p_investigation_id => 100,

10 p_pesticide_id => 123,

11 p_spray_id => 789

12 );

13

14 investigation_mgr.pack_details(

15 p_investigation_id => 100,

16 p_pesticide_id => null,

17 p_spray_id => 789

18 );

19* END;

Example data created by calls...

ID INVESTIGATION_ID SPRAY_ID PESTICIDE_ID

---------- ---------------- ---------- ------------

1 100 789 123

Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

↑ sf_epa_investigations

↓ Simple Category Sets

↓ Composite Category Sets

↓ Scenario Category Mapping

In this section we identify the category sets for the problem, and tabulate the corresponding categories. We need to consider which category sets can be tested independently of each other, and which need to be considered in combination. We can then obtain a set of scenarios to cover all relevant combinations of categories.

In this case, we have as inputs a pair of identifiers, spray id and pesticide id, linked to an investigation id, in the form of existing records in a table, and also as a single parameter triple.

It may be helpful first to consider each of the two identifiers separately, and obtain single identifier category sets with associated categories. However, we also need to consider the identifiers as pairs, as they may interact; for example, if neither parameter has a slot available we need to insert a new record, but only one.

Simple Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

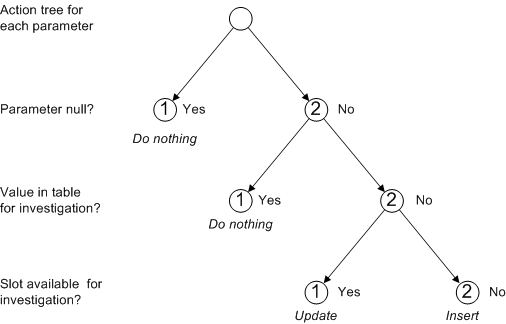

First we consider simple, single identifier category sets.

- Parameter null?

- Yes

- No

- Parameter value in table for investigation?

- Yes

- No

- Slot availabile for investigation?

- Yes

- No

The categories result in actions for the parameter value in relation to the table:

- Actions

- Do nothing

- Update

- Insert

We can represent the categories with associated actions in a dependency tree:

We will clearly want to ensure that each leaf node for each parameter is represented in a test scenario. However, while the action tree fully represents the required actions for the categories shown, there remain categories of input data that we would like to test are handled correctly. For example, the node corresponding to the Insert action could arise because there are no records in the table for the investigation, or it could arise because there are records but all have values for the parameter. It’s possible that the program could behave correctly for one but not for the other.

- Slot unavailable cases

- No records in table

- Only records for another investigation, with slot available

- Records for another investigation, with slot available, and for current investigation with no slots

Now, let’s write out a consolidated list of categories by set with short codes for ease of reference:

PNL - Parameter null (for S and P: PNL-S, PNL-P)

| Parameter Null? | Null/Not null |

|---|---|

| Y | Null |

| N | Not null |

ACT - Action with subdivisions (for S and P: ACT-S, ACT-P)

| Code | Action | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| NPN | Nothing | Parameter null |

| NVT | Nothing | Value in table |

| UPD | Update | Slot available |

| INR | Insert | No records in table |

| IOR | Insert | Only records for another investigation, with slot available |

| INS | Insert | Records for another investigation, with slot available, and for current investigation with no slots |

NUI - Simple action (for S and P: NUI-S, NUI-P)

This simpler actions category set may be useful for considering action combinations in the next section.

| Code | Action |

|---|---|

| N | Nothing |

| U | Update |

| I | Insert |

Composite Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

As noted above, we need to account for possible parameter interactions, by considering category sets for the identifier pairs.

PPN - Parameter Pair Nullity Category Set

This category set contains all combinations of null and not null for the pair of parameters.

| Code | Spray | Pesticide | S-Null? | P-Null? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YY | Y | Y | Null | Null |

| NY | N | Y | Not null | Null |

| YN | Y | N | Null | Not null |

| NN | N | N | Not null | Not null |

PPA - Parameter Pair Actions Category Set

This category set contains all combinations of the simple action category set (NUI) for the pair of parameters.

| Code | Spray | Pesticide | S-Action | P-Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NN | N | N | Nothing | Nothing |

| NU | N | U | Nothing | Update |

| NI | N | I | Nothing | Insert |

| UN | U | N | Update | Nothing |

| UU | U | U | Update | Update |

| UI | U | I | Update | Insert |

| IN | I | N | Insert | Nothing |

| IU | I | U | Insert | Update |

| II | I | I | Insert | Insert |

Scenario Category Mapping

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

We now want to construct a set of scenarios based on the category sets identified, covering each individual category, and also covering combinations of categories that may interact.

In this case we want to ensure each identifier has all single-identifier categories covered, and also that both of the identifier pair category sets are fully covered. We can achieve this by creating a scenario for each PPA composite category, and choosing the other categories appropriately, as in the following table:

| # | PPA | PPN | ACT-S | ACT-P | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NN | YY | NPN | NPN | NPN-NPN: S, P - parameter null |

| 2 | NU | NN | NVT | UPD | NVT-UPD: S - value in table, P - update slot |

| 3 | NI | YN | NPN | IOR | NPN-IOR: S - parameter null, P - records for other investigation, with slots |

| 4 | UN | NY | UPD | NPN | UPD-NPN: S - update slot, P - parameter null |

| 5 | UU | NN | UPD | UPD | UPD-UPD: S, P - update slot |

| 6 | UI | NN | UPD | INS | UPD-INS: S - update slot, P - records but no slots |

| 7 | IN | NN | INS | NVT | INS-NVT: S - records but no slots, P - value in table |

| 8 | IU | NN | IOR | UPD | IOR-UPD: S - records for other investigation, with slots, P - update slot |

| 9 | II | NN | INR | INR | INR-INR: S, P - no records |

sf_sn_log_deathstar

↑ SCAN Examples Of Use

↓ Example Data and Solution

↓ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

The sf_sn_log_deathstar subproject concerns the reading of records from a master table and two detail tables each linked by a key_id field, and the writing out of the records from each detail table into two corresponding files without duplication.

Example Data and Solution

log_deathstar_room_access

KEY_ID ROOM_NAME CHARACTER_NAME

------ --------------- ---------------

1 Bridge Darth Vader

Bridge Mace Windu

2 Engine Room 1 R2D2

log_deathstar_room_actions

KEY_ID ACTION DONE_BY

------ -------------------- ---------------

1 Activate Lightsaber Darth Vader

Activate Lightsaber Mace Windu

Attack Mace Windu

Enter Darth Vader

Enter Mace Windu

Jump up Darth Vader

Sit down Darth Vader

2 Beep R2D2

Enter R2D2

Hack Console R2D2

10 rows selected.

log_deathstar_room_repairs

KEY_ID ACTION REPAIR_COMPLETI REPAIRED_BY

------ -------------------- --------------- ---------------

1 Analyze 53% The Repairman

Fix it 95% Lady Skillful

Inspect 50% The Repairman

Investigate 57% The Repairman

2 Analyze 25% The Repairman

Fix it 100% Lady Skillful

6 rows selected.

It then calls the packaged procedure to be unit tested later, reports the results, and rolls back the test data. The script reports the results as follows:

File room_action.log has lines...

=================================

1|Bridge|Darth Vader|Enter

1|Bridge|Darth Vader|Sit down

1|Bridge|Mace Windu|Enter

1|Bridge|Mace Windu|Activate Lightsaber

1|Bridge|Darth Vader|Jump up

1|Bridge|Darth Vader|Activate Lightsaber

1|Bridge|Mace Windu|Attack

2|Engine Room 1|R2D2|Enter

2|Engine Room 1|R2D2|Hack Console

2|Engine Room 1|R2D2|Beep

.

File room_repair.log has lines...

=================================

1|Bridge|50%|The Repairman|Inspect

1|Bridge|53%|The Repairman|Analyze

1|Bridge|57%|The Repairman|Investigate

1|Bridge|95%|Lady Skillful|Fix it

2|Engine Room 1|25%|The Repairman|Analyze

2|Engine Room 1|100%|Lady Skillful|Fix it

Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

↑ sf_sn_log_deathstar

↓ Simple Category Sets

↓ Composite Category Sets

↓ Scenario Category Mapping

In this section we identify the category sets for the problem, and tabulate the corresponding categories. We need to consider which category sets can be tested independently of each other, and which need to be considered in combination. We can then obtain a set of scenarios to cover all relevant combinations of categories.

In this case we have two sets of records each independently linked to sets of master records. This means that categories for the detail entities may depend on those for the master entity.

However, it may be helpful first to consider simpler category sets, where each entity is considered separately, or where the detail entities are considered as a pair. We can then go on to consider master-detail multiplicity category sets.

For convenience, let’s use a short code for each entity:

- ACC: Room Access

- ACT: Room Action

- REP: Room Repair

Simple Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

In this section we identify some simple category sets to apply.

SIZ - Size of values

We want to check that large values, as well as small ones, don’t cause any problems for each entity such as value errors. We can do these in parallel across the entities, and also across other category sets.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| S | Small values |

| L | Large values |

MBK - Multiplicity By Key (MBK-ACC/ACT/REP)

We want to check behaviour when there are 0, 1, or more than 1 records for each entity by key, with upto 2 keys.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No records |

| 1 | 1 record for 1 key |

| 2 | 2 records for 1 key |

| 1-2 | 1 record for 1 key, 2 records for a second key |

SHK - Shared Keys

The records for ACT and REP detail entities can reference the same key as referenced by the other, or the key can be unique to one or other. We would like to check the different possibiities.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Y | Shared key only |

| N | Unshared keys only |

| B-A | 1 key shared, ACT has 1 unshared key |

| B-R | 1 key shared, REP has 1 unshared key |

Composite Category Sets

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

In this section we consider the multiplicity category sets for the detail entities (ACT, REP) in relation to the multiplicity category for the master entity (ACC).

ACC-0 - Empty

Where there is no ACC record there can be no ACT or REP records either.

| MBK-ACT | MBK-REP |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

ACC-1 - 1 ACC record

Where there is 1 ACC record there can be 0, 1 or 2 ACT or REP records. We could check the different possibiities in parallel, as we will be looking at combinations later, or we could even just explicitly check the 1-1 pair.

| MBK-ACT | MBK-REP |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

ACC-2 - 2 ACC record for same key

Where there are 2 ACC record there can be 0, 1 or 2 ACT or REP records. We can check the different combinations of ACT and REP multiplicity here, with 0, 1 and 2 available, while the 2-key category 1-2 is not possible.

| MBK-ACT | MBK-REP |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 |

| 2 | 2 |

ACC-1-2 - 1 ACC record for 1 key, 2 records for a second key

Where there is 1 master (ACC) record for 1 key, and 2 records for a second, the shared key (SHK) categories for the detail pair (ACT, REP) can be tested, as shown in the table.

| SHK | MBK-ACT | MBK-REP |

|---|---|---|

| Y | 1-2 | 1-2 |

| N | 1 | 2 |

| B-A | 1-2 | 1 |

| B-R | 1 | 1-2 |

Scenario Category Mapping

↑ Scenario Category ANalysis (SCAN)

We now want to construct a set of scenarios based on the category sets identified, covering each individual category, and also covering combinations of categories that may interact.

In this case, the first four category sets may be considered as a single composite set with the combinations listed below forming the scenario keys, while the two SIZ categories are covered in the first two scenarios.

| # | MBK-ACC | MBK-ACT | MBK-REP | SHK | SIZ | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 0 / 0 / 0 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Y | L | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 1 / 1 / 1 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / L |

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 0 / 0 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 0 / 1 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 0 / 2 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 1 / 0 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 1 / 1 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 8 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 1 / 2 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 2 / 0 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 10 | 2 | 2 | 1 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 2 / 1 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 11 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 2 / 2 / 2 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 12 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | Y | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 1-2 / 1-2 / 1-2 ; SHK / SIZ = Y / S |

| 13 | 1-2 | 1 | 2 | N | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 1-2 / 1 / 2 ; SHK / SIZ = N / S |

| 14 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1 | B-A | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 1-2 / 1-2 / 1 ; SHK / SIZ = B-A / S |

| 15 | 1-2 | 1 | 1-2 | B-R | S | MBK - ACC / ACT / REP = 1-2 / 1 / 1-2 ; SHK / SIZ = B-R / S |

Mapping Scenarios to Categories 1-1

↑ Contents

↓ Generic Category Sets

↓ Categories and Scenarios

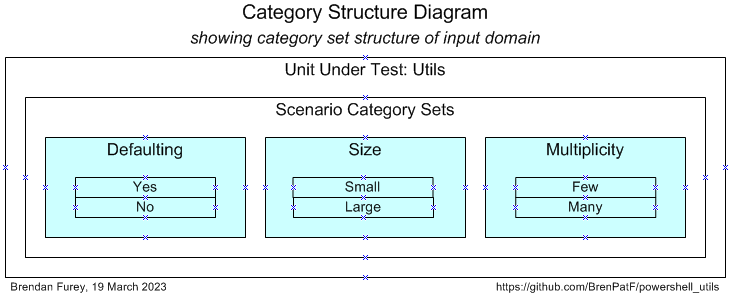

While the examples above aimed at minimal sets of scenarios, we have since found it simpler and clearer to use a separate scenario for each category. In this section I show how this works using an example of testing a set of generic Powershell utility functions.

In addition, I introduce a new diagram that I have found very useful to display categories within category sets.

This section is largely copied from the GitHub README:

Generic Category Sets

↑ Mapping Scenarios to Categories 1-1

As explained earlier, it can be very useful to think in terms of generic category sets that apply in many situations. In this case, where we are testing a set of independent utilities, they are particularly useful and can be applied across many of the utilities at the same time.

Binary

There are many situations where a category set splits into two opposing values such as Yes / No or True / False. In this case we can use it to apply to whether defaults are used or override parameters are passed.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Yes | Yes / True etc. |

| No | No / False etc. |

Size

We may wish to check that functions work correctly for both large and small parameter or other data values.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Small | Small values |

| Large | Large values |

Multiplicity

The generic category set of multiplicity is applicable very frequently, and we should check each of the relevant categories. In some cases we’ll want to check None / One / Multiple instance categories, but in this case we’ll use Few / Many.

| Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Few | Few values |

| Many | Many values |

Categories and Scenarios

↑ Mapping Scenarios to Categories 1-1

After analysis of the possible scenarios in terms of categories and category sets, we can depict them on a Category Structure diagram:

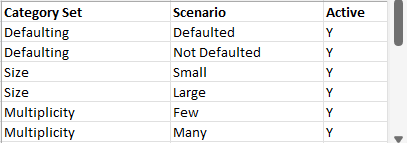

We can tabulate the results of the category analysis, and assign a scenario against each category set/category with a unique description:

| # | Category Set | Category | Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Defaulting | Yes | Defaulted |

| 2 | Defaulting | No | Not Defaulted |

| 3 | Size | Small | Small |

| 4 | Size | Large | Large |

| 5 | Multiplicity | Few | Few |

| 6 | Multiplicity | Many | Many |

From the scenarios identified we can construct the following CSV file (ps_utils_sce.csv), taking the category set and scenario columns, and adding an initial value for the active flag:

There is a Powershell utility API to generate a template for the JSON input file required by the design pattern:

The API can be run with the following powershell in the folder of the CSV files:

Format-JSON-Utils.ps1

Import-Module TrapitUtils

Write-UT_Template 'ps_utils' '|'

This creates the template JSON file, ps_utils_temp.json, which contains an element for each of the scenarios, with the appropriate category set and active flag, with a single record in each group with default values from the groups CSV files. The template file is then updated manually with data appropriate to each scenario.

Conclusion

In this article, we started by noting that unit testing against infinite input spaces can be reduced to testing sample data points from a finite number of domain partitions; we then showed how the concept of input data categories and category sets can be used as a practical way to construct unit test scenarios, with several examples; we proceeded to define the approach more precisely as the SCAN method, with three worked examples.

The SCAN method does not depend on any testing framework, and in fact can be used with manual unit testing. However, for more rigorous multi-scenario testing we can see the benefits of automation.

The The Math Function Unit Testing Design Pattern allows for writing of unit test functions whose complexity:

- depends only on the inputs and outputs of the unit under test

- is independent of the internal complexity of the unit under test

The data-driven nature of the Math Function Unit Testing design pattern means that once the unit test function is written any number of scenarios can be tested simply by adding records to the input JSON file.

See Also

- The Math Function Unit Testing Design Pattern

- Database API Viewed As A Mathematical Function: Insights into Testing

- Trapit - JavaScript Unit Tester/Formatter

- Powershell Trapit Unit Testing Utilities module

- Trapit - Oracle PL/SQL unit testing module

- Oracle Unit Test Examples

- Utils - Oracle PL/SQL general utilities module

- Oracle PL/SQL API Demos - demonstrating instrumentation and logging, code timing and unit testing of Oracle PL/SQL APIs

- Timer_Set - Oracle PL/SQL code timing module

- Log_Set - Oracle logging module

- Powershell General Utilities module